|

|

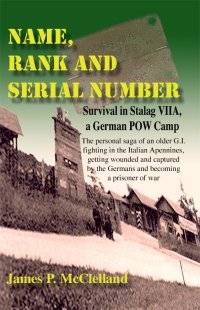

| Stalag VII A: Oral history |

| James P. McClelland |

POW No. 131313My father, James P. McClelland from Temple City, California, was a 35-year-old private in the U. S. Army when he was wounded and captured in the Italian Apennines north of Florence on October 11, 1944. He was fighting with the Fifth Army's 88th Division, 351st Regiment. He was eventually transferred to Moosburg and Stalag VII A. Jim was an ordinary Californian who wound up in extraordinary situations as a result of joining the Army and being sent into action in the Italian campaign. He was thrust into some of the bloodiest fighting of World War II. After the war, my father put his experiences on paper. He tried to publish his story, but his inexperience as a writer meant he would get one rejection slip after another. He gave up on publishing his story, but the actual writing seemed to have a therapeutic effect on him. He got the war off his chest. Dad's manuscript rested in a box in a closet in my house after his death in 1973. Thirty years later, I was motivated after watching the film "Saving Private Ryan." I reread Dad's story and realized what a poignant piece of information it was. My father's limited education prevented him from explaining clearly what had happened in the war. I decided to edit his work. It took three years before it was ready to print. I had visited what was left of Stalag VII A and visited the museum in Moosburg. I walked the streets of Munich where Dad had dodged allied bombs, even stood on Gesso Ridge in the Apennines, close to the place where he had fought his last battle. I searched on line, read scores of books on the war in Italy, talked to former POWs, and finally finished his story.

NAME, RANK AND SERIAL NUMBER was published in November 2005. It is available via this book order form (PDF). Following are some excerpts from the book, especially parts that relate to life at Stalag VII A: Excerpts from Chapter 3 of NAME, RANK AND SERIAL NUMBER (The prisoners were en route from Italy by train, a long journey with almost nothing to eat.) The door was closed and boarded over once more, and the train began its descent through a corner of Austria and onward toward Germany. We groaned through the long night. The train groaned along with us. After suffering through the ungodly trip, our train stopped at a little station, hopefully our final destination. A sign on the station's platform indicated we were in Moosburg, Germany. It appeared we were not going to a farm. As the guards with their dogs on leashes directed us, we disembarked our last-class rail cars. We were a tired, hungry belligerent group. We were ready to make a run for it. We had talked about overtaking the guards, knowing we would lose some lives in the process. We would have to deal with the dogs, too, but we did outnumber the combined total of guards and dogs, probably ten to one. Not one break was made, however. Like sheep, our flock of prisoners walked solemnly to an open area. We were separated into groups of one hundred twenty men. We noticed there were fewer guards here than we had in Italy. Joe, Jimmie and I had stayed together. What a sad-looking group we were. We had long faces, dirty hands, long beards, bodies that hadn't been bathed in weeks, and, more than anything else, stomachs that ached for food and water. A wagon with a big tank of water was brought into the camp. We were forced to stand in a single line to get one dipper of water. The line was endless, mainly because we would get our water and get back in line. After quenching our thirst, at least temporarily, few hours passed. We were issued a spoon and a small bowl. They had not been cleaned since their last use, so we used dirt and sand to remove the mold and decay in our new utensils. Optimistically, we thought our utensils indicated food would be forthcoming.A couple more hours passed - it was well past midday - and a portable soup wagon arrived just outside our fenced-in area. Big cans of soup were passed inside and we grabbed for them. Many of the cans had small holes in them, and soup was dripping out of them. This was a living nightmare. As starved as we were, we wanted every drop of soup that was available. It was a frustrating experience, an intolerable existence. Every time we thought we were to get food, something happened. This time it was soup seeping out of holy cans. Amen. The dispensing of soup was halted, and several guards came through the gate, their bulging coats concealing something. We would soon find out they had loaves of bread they were willing to trade with any POWs who had managed to keep anything of value. A watch, a ring, even a fountain pen would be worth a loaf of bread. At the time, bread had more value than anything we owned. And the guards knew it. Surprisingly, some prisoners did have items to trade. But not our trio of buddies. When the trading session was concluded the distribution of soup resumed. More cans were passed through the fence. Luckily, Joe, Jimmie and I got a can that was intact and contained thick soup. It was a comparable feast for us. After consumption of our one-course meal, we were taken to an open shed where there were many bales of straw. We formed it into makeshift beds and spent a cold night huddling together on the ground, seeking sleep and warmth. We couldn't get much of one without the other. Daybreak greeted us with a blast of Bavarian mist, cold and damp. When we rose to face our next day, we had to be careful. Sudden moves, like standing up, would make us dizzy. We were feeling faint. One bowl of soup during the previous day had not made us strong men. We learned we were in an area inside a prison camp known as the Nordlager where newly arrived prisoners were to spend two days. We were broken into small groups and taken inside a small building. Our processing included fingerprinting and taking of ID photos. We held a big card in front of our faces, the card showing our assigned prisoner numbers. I wondered about my luck when I learned of my number: B131313. That was a lot of thirteens, a number often thought to be unluckiest of all. I was born on the thirteenth of March, though, so I kept positive thoughts about the three connected thirteens. Our complete processing included a brief medical examination with no cleaning of wounds. Joe and I were well on the road to healing, but Jimmie could have used some treatment. He had lost his temporary crutches long ago, but he managed to hobble quite well. He never wanted to be left behind. We were stripped and deloused, a first-time experience for us. There were no showers. The process was completed in no rush, we were marched a few hundred yards to the main prison camp of Moosburg. We got our first look at a bona-fide German camp for prisoners-of-war - a compound built for one purpose: to incarcerate POWs. There was one machine gun-manned tower at the main entrance where we entered Situated in a flat area surrounded by hills, the camp was roughly a square divided into three main compounds. We saw scores of wooden barracks with the obligatory double rows of high barbed wire fences encircling the whole camp. It was formidable. There were few guards. There was good reason. The camp had been constructed to contain prisoners. It might as well have been Sing Sing. When the iron gates clanged shut behind us, they made an audio explanation mark for our sentence of undetermined length. We had been through some temporary confinement in Italy, even in the "cattle cars" on the rails through the Brenner, but this looked to be a good-bye to the outside world. This was our so-called farm. That was like calling an insane asylum a funny farm. Ours would be a farm where nothing would be planted, nothing would grow. The last words from our guard were that we would be safe here. He must have meant safe from escaping. We were safe and secure, no doubt about it. If home is where you make it, we were in our new home - and didn't know if we would make it - and we had no idea how long we would be here. Excerpts from Chapter 4 of NAME, RANK AND SERIAL NUMBER (Boring life at Stalag VII A continued.) Several times during our days in the barracks, a guard named Heinz would check to see if all was well. He was a small, stubby man in his early forties. His oversized gut looked like it would pull him over forwards. His uniform fit poorly. His neck was so short it appeared as if his head rested on his shoulders. He had a reddish, round face and an ever-present smile that revealed two gold teeth. He was proud of those teeth. He spoke very little English, just occasional words, most of which we were teaching him. In return he taught us German phrases and swear words. It was a fair-trade agreement. His mind ran toward the dirty side. One of the first words he taught us was scheiße - shit. Kacke, we soon learned, was a more vulgar way to say doo-doo. We were on our way to becoming outhouse linguists. We even learned a few dirty phrases, such as Und wenn Du mich schlägst, ich weiß - It beats the shit out of me! On his first visit someone nicknamed him "Stubby" and the name stuck. Jimmie kept a straight face when he told Stubby that the English word "pig" meant "wonderful." Stubby went everywhere saying Hitler was a pig. The guards at Stalag VII A were either very young or exceedingly old. They were unfit for duty at the front so they served where they were needed. Many had been wounded so severely that they could not return to active duty. They became guards. Most of the guards tried to be fair with prisoners, at least with American and British captives. The Russians, we were told, did not get a fair shake. Germans thought of Russians as beasts and they treated them as if they were wild animals. Guards became nervous about how their commanding officers would rate them. There was always the threat of being sent to another camp near the Russian front. None were anxious to be in a P.O.W. camp that might evenually be liberated by Russian troops. One late afternoon we were taken to a supply tent to be issued overcoats. Since I was near the end of the line, there wasn't much choice when my turn came. At first they issued me a very small coat. Trying it on, the sleeves came just below my elbows. Stubby had taught us that the German word for large was gross. I handed the coat back to the supply sergeant and told him I needed a gross coat. My only choice was the exact opposite of the first coat. The German soldier brought out a Russian great coat. It was so long its tail dragged on the ground. I had to roll the sleeves back to use my hands. That was the best my Moosburg tailor could do. Little did I realize my good fortune in getting such a gross coat. It had advantages. It could be used as an extra blanket in the cold months ahead. With its extra bulk it would be easy to conceal food and other articles to smuggle past the guards. I looked like a character from one of the Bill Mauldin cartoons, but I was satisfied. We would have no fashion shows at Stalag VII A. The day after getting my gross coat, we were taken out of camp on a work detail. We liked getting out of camp. Work was exercise, and we might even scrounge around and find something edible. Some firewood would be a good find, too. We hiked for fifteen minutes, passing through the delightful village of Moosburg. There was no sign of war. Our march took us over the Isar River to a big farm. Our job was to dig shallow trenches, toss in potato pieces, each with an eye showing on it, and cover them with a layer of straw and loose dirt. We were planting potatoes. We were amazed at what we saw in the field. For his tractor a German farmer had a big plow and two animals to pull it: one horse and one cow. That was his team. Back home we had mechanized tractors for such a job. We didn't know if this one farm was a rarity, but it was a weird combination. It drew much laughter from our group, but we were quieted by threats from our guards. This was the first time my gross coat - or great coat - would come in handy. I dropped several potatoes in the legs of my fatigues and smuggled them back to camp camouflaged under the gross coat. Later we would cook them over coals in our stove. It was easy for me to make friends at that time. A baked potato was a treat. Our next work detail came as a surprise one morning when Stubby made his daily visit to our barracks. He took Jimmie, me and four others out the main gate where a more serious armed guard took over. We were assigned to dig machine gun emplacements at one corner outside Stalag VII A. P.O.W.s were not supposed to be used for such military labor, according to the Geneva Agreements, yet the Germans had no fear of reprisal. The Germans paid no attention to international law. Neither did we for that matter. We dug and we dug. We ran wheelbarrows of dirt. In our rundown condition, we became extremely tired. Our backs ached. Our guard was a tyrant. He demanded we work faster and carry more dirt with each wheelbarrow load. We were out of sight of the closest guard tower and were being watched by only one guard. He carried a rifle. Not fifty yards from us there was a thick growth of timber, so we were not long in making plans to overpower the guard, catch him relaxing, and make a run for the woods. We didn't know where we would go when we got to the woods, but it was a chance we considered taking. If the forest turned out to be thick enough, we could hide until dark. We might have a chance, we figured. We agreed to make a try of it. The plan was simple. Jimmie and I would push our wheelbarrows near the side of our guard. We would fake an argument and get into a fight. As soon as the guard turned to stop us, the other four would overpower the guard. They would take his rifle and ammunition, and we would run for the woods. We made the wheelbarrow trip several times before getting the nerve to finally try our plan. All the while, Jimmie and I were exchanging angry comments, setting up the eventual fight. Finally, we agreed it was time to perform. I pushed my load down a bank, and I heard Jimmie's wheels grinding in the loose gravel. He was right behind me. I yelled at him to get the hell off my tail. We won't repeat what he said back to me, but it was a fine performance. I dropped my handles and turned to face Jimmie. It was time to fight, and we were determined to make it as real as possible. Before I could take a swing at Jimmie, several officers on horseback appeared. They were accompanied by a dozen dogs. They rode past us, down the road, disappearing over a small hill. Unknowingly, they eliminated our desire to escape, at least on this day. The dogs were the main consideration. We said little to each other, just went on with our labor. Jimmie and I never fought one another. We joked later about who would have won the fake fight. I would have bet on Jimmie. He was much younger than I and he was definitely in the heavyweight class. Camp routine was ever so monotonous over the next couple of weeks. There were no real work details other than some occasional trips to get firewood. Many of us were not fortunate enough to get the assignment. Morale, which had been relatively high in camp, sunk to a new low when we were cooped up in our barracks for long hours. We lost our enthusiasm. Men would sit on the edge of their bunks and stare at the floor, walls or ceiling. Take your pick. We had one deck of cards and the most men we could include in a game was six. If a player left the game for any reason, he would forfeit his seat to the next in line. Spectators would watch the game closely, waiting for someone to get squirming over a call from Mother Nature. The cards were becoming as battered and worn out as we were. GIs resorted to some off-color games, anything to fill time. Some of the younger ones would stage farting contests. One scrawny little guy would drop his pants, stand on our lone table, bend his knees and let blast with a big one. One time he lit a match at his butt, but there was no explosion. Being short of food we were, alas, short of gas. Several times a day we were called outside for roll call. Rain, snow or severe cold, the count had to be made. We were a shabby-looking lineup of soldiers. Long, unkempt hair protruded out from under our caps. We were usually unshaven. Our few dull blades and the availability of a rough, sandpaper-like bar of soap made shaving a true ordeal. We avoided shaving unless it was ordered of us. Our clothing was unruly, unlaundered. One Sunday night, Stubby came through the barracks on his regular visit and told us that the next morning our compound was to furnish one hundred volunteers to go to Munich and work for a day. He made it clear that we could not be forced to work. If he failed to get enough volunteers, however, he would have to schedule an inspection of the barracks and it would be necessary for the troops to stay outside in the cold all day. Stubby didn't need to threaten us. We were excited about going to Munich. We knew we wouldn't be visiting the famous beer halls or seeing the sights, but a trip to Munich beat staying in Moosburg, cooped up in Stalag VII A. Munich would offer a change of scenery, an escape from boredom. We had heard that Allied bombers had wreaked havoc on the city. We would see for ourselves. And there was always a chance that we would find some extra food.It seemed like the middle of the night when Stubby came to roust us from our slumber. It was 4:00 A.M. He shouted, "Raus mit you. Up gets!" We dressed quickly, stepped outside where we received our breakfast: lukewarm imitation coffee. How could they expect us to work all day in the capital of Bavaria on empty stomachs? There would be no answer to our question. Call it rhetorical. We had two inches of fresh snow on the ground as we stood for our morning roll. We buttoned up our overcoats. All were present and accounted for, but they held us in the ranks for about an hour. When our group marched down the prison's main boulevard and out the front gate, we were joined by about twenty other groups of volunteers. We would be taking more than two thousand workers to Munich. There were more guards than usual for this special assignment. They concentrated on keeping us in our original groups and making certain we were all there. At the prison train station they had forty freight cars waiting on a siding for us. So much snow had drifted in the big side doors of the freight cars, they looked like refrigerated units. We clambered aboard, competing for the warmest corners to sit. There were no warm corners. And sitting was not recommended. Cold air came up through the floor boards of these antique freight cars. We were forced to stand. An engine was coupled to our line of cars, and we jerked forward, some men falling. Slowly we gained momentum. There was a lot of arm-swinging and foot-stomping to try to stay warm. Before we were out of Moosburg, Jimmie, in his high tenor Southern voice, started singing "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot." Other picked up on the melody and eventually we had most of the volunteers singing in unison, loud and clear. We followed with some spirituals and popular Hit Parade songs. The clackety-clack of the railroad track gave us the beat. Our old freight car was swinging and swaying as we made our trip southwesterly to Munich. Three guards rode with us, staying near the open door. They were armed, of course. The guards were enjoying our singing. They smiled broadly. At one break in songs, the three of them sang a German song. We established camaraderie, for the moment at least, that would make us forget we were enemies. Through song and good spirit, we were one happy bunch. Song leader Jimmie took a risk when he started bellowing the satirical "Heil, Heil right in the Fuehrer's face." The Germans applauded and cheered when they heard us singing of their Fuehrer. They thought it was a tribute. We covered about twenty-two miles in three hours. At our final destination within the city limits, we disembarked. Our group formed ranks at the side of the tracks. It was good to see civilians going about their daily routine. As we marched down a wide strasse, it was our first viewing of German people. The buildings seemed different than what we had at home, and the people dressed differently. But, for the most part, they looked just like folks back home. It seemed most of the civilians were women. Lots of younger men in uniform were evident, too, many of them back from the front. There were men on crutches, some with missing limbs, all showing the mental and physical damage inflicted by combat. And these were the lucky ones, the soldiers who got to come home. Entire city blocks had suffered damage, too. Some buildings were reduced to piles of rubble. As a group, the German women appeared clean and neatly dressed. They paid little attention to us. The bombing of Munich had gone on for weeks, and living amidst a war-torn city had become a common, almost normal, activity. They had no doubt seen lots of prisoners. The guards may have been trying to convince the locals that Germany had great numbers of prisoners, implying that they were winning the war. No amount of propaganda would work now. People were surviving in the remains of what was once a proud city. Many were obviously homeless. Friends and family had been killed in the bombings. It was devastating for them. Excerpts from Chapter 6 of NAME, RANK AND SERIAL NUMBER. (Jim and his two buddies had been transferred to Munich for permanent duty as work commandos. The lived in a Munich confine. They worked for a gestapo agent named Heinrich, doing all kinds of odd jobs.) Hilda came to the garage about noon and offered to take us for our soup call. Wanting nothing to do with us and happy to avoid the walk, Heinrich agreed. Our walk would take us through a long tunnel that goes under the marshalling yards of the railroad, but the previous day's bombs had completely closed the passage. Hilda knew best; it was detour time. She led us south through littered streets, making our way to the front of the destroyed station. Several hundred American GIs were passing and we came to a stop to watch them. We heard from a German passerby they were captured at the Battle of the Bulge. Suddenly the soldiers halted and a German officer focused on us. He walked to us and barked, "Fall in on the end of the line." Joe and I were panicked. We were about to be captured for the second time. Hilda was searched thoroughly and one German threw her identification card on the ground. She had tried to explain our situation, but no one was listening. Hilda became indignant and shouted German obscenities at the top of her voice. They paid no heed to her, even threatened to imprison her if she didn't leave. Hilda walked away. We joined the ranks and followed the new POWs down the street, not knowing where we would be going. One of the guys ahead of us said he thought we were going to a concentration camp in Moosburg. We never expected to see that place again. The man's prediction seemed to be quite possible. We were loaded in box cars and a train started pulling us in a direction with which we were all to familiar. It was after dark when we made our unheroic return to Moosburg. While all the other troops were processed for imprisonment, Joe and I were handcuffed and taken to a small room where we were searched. After that two guards marched us into the camp, but we didn't return to our old barracks. Instead we were placed in an isolated building with bars on the windows. They took us down a long hallway and locked us in a very small cell. We were in the Sonderbarracke, a special detention jail for POWs who had tried to escape. While living in Stalag VII A we had heard rumors about this place and the harsh treatment that was dished out. The square room was about six by six feet in size. A bare bulb hanging from a high ceiling revealed one small, barred window. An old slender bench made of wood was only four feet long. Under it was one dirty tattered blanket and a smelly bucket - our toilet. High on the door was a peep hole. We were told to stand and face away from the hole whenever a guard approached. What a lovely hell hole! We had gone full circle back to Moosburg, escaping Allied bombing while being placed in semi-solitary confinement. The guards had given us a Bible, God bless them. Under the dim light, we took turns reading the scriptures. We tried to get some sleep, but the cold and severe hunger pangs prevented it. Hours dragged by and we talked of homes we might never see again. The optimism we had developed in Munich faded. The next afternoon our door opened enough for someone to push forward a pan with something in it. The door was closed quickly and we reached for our food. The pan held six green beans resting in clear water. Twenty-four hours passed before the lock on the door was rattled again. Half facing the door as it opened I saw a GI who pushed another pan of beans to us. In a low voice I asked him how long we might be kept in this place. The skinny man had no idea. "I've been here about six months and I've never had a trial." "What did you do?" I asked. The door closed and Joe and I sat on our little bench and stared at one another. We realized we would not last long on our skimpy green bean diet. We would die of starvation in this dingy dungeon-like cell. Later that day two guards came to get us. With no explanation we were handcuffed, taken from our cell, led out the main gate, taken to the Moosburg camp's train station. The guards boarded a train with us, finding soft seats in a coach car. It was quite a luxury, even in handcuffs. The guards were happier than would be normal. A small bottle of cognac was consumed by them as we railed toward our destination: Munich. At the end of the line we were marched several blocks to an old stone jail. We were told to remove our shoes. Then we were placed in a big room with thirty others. They were POWs of every race and nationality. Besides being prisoners of the Germans, they had one other thing in common: They had been caught trying to escape. We would be living in squalor once again. The room was furnished with rickety wooden bunks and blankets infested with lice. No air raid shelter was assigned to us. On our second night there we hid under our thin mattresses as bombs landed nearby. Some of our cellmates told us they had been waiting for two weeks to be taken to court. They were to be tried as attempted escapees. They were naturally worried over the eventual outcome. Joe and I lost track of time while we waited for our turn. Each day a group would be taken and marched away from the quarters. We never knew what happened to them. We only knew they never returned. Our one meal a day was skimpier than ever. Excerpts from Chapter 7 of NAME, RANK AND SERIAL NUMBER (Jim McClelland and his two closest POW buddies were in a Munich shelter during their last night of captivity.) From our confined space, we saw the most welcome sight of our lives. A sergeant with two privates, all carrying tommy guns, came cautiously down the stairs. Our guards threw up their hands, surrendered without a second thought. In a moment of joy, several of us rushed the GIs to thank them. "Stay back," said the sergeant. "Some of them may still want to fight." We assured our liberators that there was no fight left in the guards. All were present and accounted for. Our liberating soldiers were with the 42nd Rainbow Division. We would remember them. We were free to go up the stairs to a Munich that was being liberated. There was nothing but joy on the outside. An American tank was cruising up our street with GIs hanging on it, some with cigarettes dangling from their lips. Jeeps filled with armed American soldiers buzzed the streets. Other active GIs from the 42nd were on foot working the streets, checking buildings. We were yelling and screaming, laughing and hugging, crying and smiling. The streets were crowded with others, POWs, American soldiers and German civilians, all celebrating. The war was over in our part of the European theater. A burly Russian prisoner grabbed me and gave me a wet kiss on the cheek. His prickly whiskers and raunchy body odor did me no harm. With no hesitation, I kissed his hairy cheek in return. Jimmie, Joe and I formed a circle in the middle of the street. We threw our arms around each other, then dropped to our knees. For a minute or more, we spoke no words. We had a silent prayer, each understanding without saying it what we had been through: seven months of not knowing what our fate would be from one minute to the next. Our terrific trio - The Three Municheers - had survived the odds. We cheered with the street mob. Tears still moist on our faces, we returned one more time to our barracks. We were unbelievably thrilled to be free, taken from the shackles of imprisonment. We realized, at last, the joy of freedom. This oral history was prepared by © J. Thomas McClelland, son of Stalag VII A POW James P. McClelland. Further information:

|

| Last update 4 Jan 2006 by © Team Moosburg Online - All rights reserved! | |||